|

'The

beautiful façade of Le Monaco restaurant beckons

you to take refuge from the streams of cars and buses

which rush past along London Road, swerving dangerously

close to the pedestrians as the road turns by the restaurant.

The only other place to find some seclusion is in the

park over the road to the west.'

At

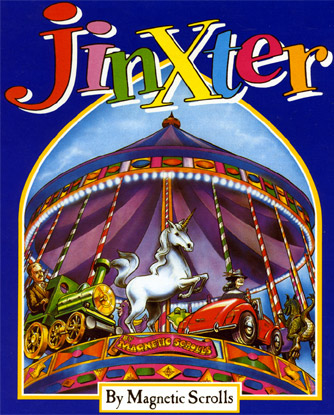

a distance of half a mile or so from this upmarket Corruption

location in the City of London, south of the river between

London Bridge and Borough station, lie the offices of

Magnetic Scrolls. Nip down a grimy side alley, pass by

a hearty-looking London pub, travel up in a rickety, rattling

lift and you're there. It's a deceptively low profile

for a company that has won practically every adventure

accolade going including the prestigious British Micro

Computing Game of the Year award for The Guild of Thieves.

So

how did this small but successful company actually start?

We spoke to Ken Gordon and Anita Sinclair.

'When

the QL came out, that looked like an opportunity for writing

new, interesting games. When the ST came along with its

added graphics the move was easy because they're both

68000 machines. There was a gap in the market; nobody

had got into 16-bit machines so we took the chance.'

They

picked adventure rather than arcade games purely as a

matter of personal preference. The product of this initial

gamble was The Pawn. Set in the mythical land of

Kerovnia, it was marketed by Rainbird and converted to

run on a wide range of 16 and 8-bit formats ranging from

IBM PC compatibles to Amstrad CPCs.

Each

game takes about a year to develop. All primary work is

carried out on a huge DEC Micro Vax linked to a series

of individual terminals. With plenty of memory and disk

space it's associated with none of the initial problems

of working within the restrictions of a smaller machine.

Disks don't corrupt and valuable bits of information don't

get lost. A couple of programmers work from home on comparatively

fast Apricot Xens, but the bulk of the programming takes

place on a system which provides more than enough opportunity

to experiment.

|

|

|

What

amounts to about 80 % of a game is written by

two people, one specializing in the text and the

other in coding but as their work overlaps, neither

is a complete specialist.

About

two months before a game is due to be released,

work starts on the individual versions. A specific

format is assigned to each programmer: Ken, for

example, has been working on the Amiga version

of Corruption, Anita Sinclair on the ST.

Meanwhile a small army of play-testers and bug-spotters

is called into action.

Quality

Control

The

care that goes into the elaborate peripherals

reflects the potential shelf life of each product.

Ken Gordon:

'Our

idea of a nice product is not necessarily one

that's going to make number one in the charts

but one that's going to sell for years. We still

sell reasonable numbers of The Pawn.'

Ken

reckons that the games have been successful because

of the amount of effort that has been put into

them:

'If

we don't get something right it (the cause of

the bug) will either come out completely or we'll

delay things so it is right. We try and produce

the most high quality product we can. We aren't

in the same business as the people who sell their

products at £ 1.99.

|

|

|

It's

in the nature of an adventure that, in comparison

with top quality arcade products, it has a longer-lasting

shelf life.

'Adventure

games tend not to have as many bells and whistles

as, say, a 3-D shoot-'em-up which needs to have

features to appeal to the next generation of game

players. Adventures don't have the same initial

sales figures but new players are still buying comparatively

old adventures for the first time.'

GAC-Mania

Over

the years they've developed a whole range of in-house

adventure utilities. What do they think of some

of the finished systems available on the market

now?

'A

lot of really good ideas get strangled because a

system isn't capable of expressing them. One of

the most complex utilities available at the moment

lets you have up to 500 flags and 500 counters -

you couldn't express one of our games in those terms.

Without that extra flexibility, I could see it being

very difficult to write a half-reasonable game using

one of the adventure writing systems. The ones I've

seen, even by people I've expected to do quite well,

have been marginal.'

Magnetic

Scrolls adventures, on practically every format

other than the Spectrum, are well-known for their

excellent illustrations. So where does Ken really

stand in the great graphics versus text debate?

|

|

|